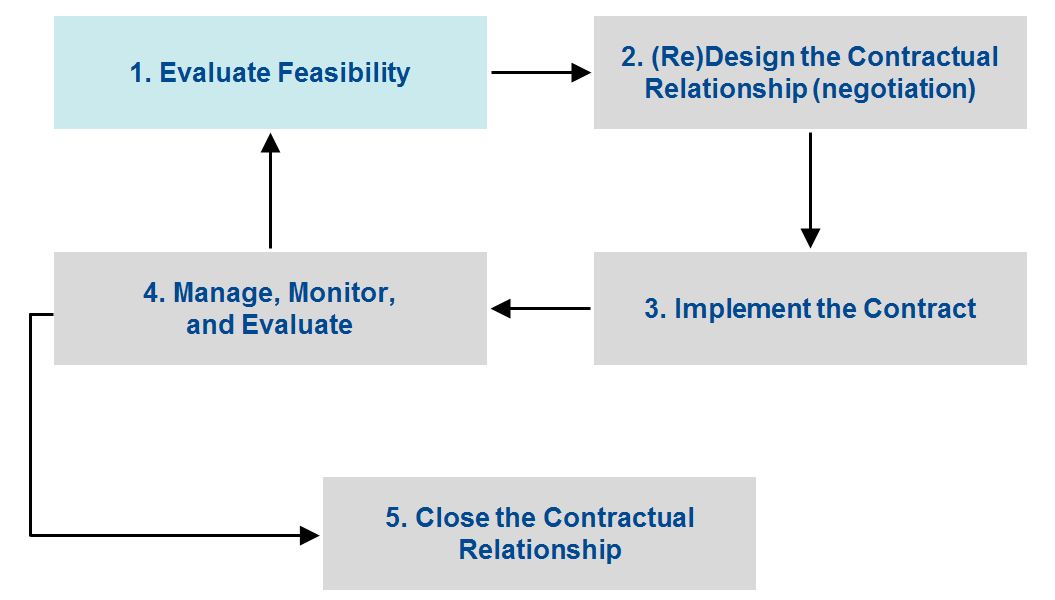

Stage One: Evaluate Feasibility

In the first stage of the contracting lifecycle, stakeholders evaluate the feasibility of entering into a contractual arrangement for family planning services. During this stage, SDOs should take stock of relevant conditions, some of which are external and others that are internal to their organization. Information gathered should help the SDO evaluate the compatibility of the contracting opportunity with the SDO’s client base, the services it offers, and its readiness to comply with the provisions of the potential contract (accreditation requirements, capacity to serve expected clients, and so on).

- 1.1 Where do I start?

- 1.2 Where do I find contracting opportunities?

- 1.3 How should I expect to be approached by purchasers to contract for services?

- 1.4 What is a Request for Proposal?

- 1.5 How can I assess my organization's capacity to contract for FP/RH services?

- 1.6 What external market indicators are relevant to evaluate the potential and feasibility of subcontracting? Where are these data found, and how are they interpreted?

- 1.7 When should I decline a potential contracting opportunity?

- 1.8 How will a purchaser evaluate my proposal?

- 1.9 What are different payment methods I can expect a contract to offer?

1.1. Where do I start?

Stage 1 of the contracting lifecycle refers to evaluating feasibility of your organization to enter into a contract. 1.3 explains in more detail how to assess your SDO’s capacity to contract for family planning services. Once you have completed this assessment, there are a few ways you can seek contracting opportunities. Depending on how the contractor is selected, a contract can be classified as competitive or sole source. In competitive bidding, a purchaser makes a selection based on factors such as the market analysis of available SDOs including their quantity, distribution, and qualifications. Sole-source selection occurs when an SDO is invited by a purchaser directly, without competition to enter into a contract. For either mechanism, an SDO must know the eligibility criteria for bidding and understand the legal requirements and their capacity to meet them (Corby, 2012).

1.2. Where do I find contracting opportunities?

SDOs can identify potential contracting opportunities from a number of sources. The most common source is external relationships with current and potential purchasers of family planning services and other relevant actors (SDO associations, community partners, and so on). Establishing a visible and strong reputation—with, for example, expertise in reaching targeted clients and delivering quality care—positions an SDO to be approached by purchasers interested in contracting out for family planning services and gaining competitive advantage when bidding for a contract.

Other sources of information on potential contracting opportunities can vary by market and should be determined as part of the research done by the SDO to assess the feasibility of contracting. These other possible sources include:

- Purchaser websites and newsletters (for example, the Ministry of Health)

- Public health organizations

- Donor websites and bulletins

- Accreditation organizations for family planning and reproductive health services

1.3. How should I expect to be approached by purchasers to contract for services?

A contract can be offered, or tendered, by a purchaser on a competitive or sole-source basis. Under competitive bidding, proposals submitted to purchasers are evaluated based on predetermined technical and cost criteria. Selection criteria of the purchaser may reflect the purchaser’s assessment of supply and demand for the service(s) being sought, as well as an assessment of bidders in terms of their qualifications, capacity and presence, cost, and reputation.

Sole-source selection occurs when a contractor is selected without competitive bidding; it is based on the contractor’s capacity, as perceived by the purchaser, to deliver the specified services (Corby, 2012).

Informal contracts also exist. These are based on non-binding arrangements, which can be written, verbal, or tacit (Liu et al., 2006). Informal contracts may be easier and faster to establish but may become problematic to manage due to lack of clarity, detail, and enforceability. Sometimes relationships between an SDO and a purchaser begin with an informal contract or agreement and then are replaced with a formal contract as time and volume under the agreement increase.

1.4. What is a request for proposal?

A request for proposal, or RFP, is a formal competitive bidding mechanism used by purchasers to solicit interest from SDOs to enter into service contracts. Although family planning and reproductive health services are currently usually contracted out using less formal methods (sole-source contracting based on existing relationships, for example), it is foreseeable that use of more formal contracting approaches, including RFPs, will increase as governments and donors expand purchasing of family planning and reproductive health services and their contracting sophistication grows.

An RFP enables SDOs to identify prospective purchaser partners and to obtain information about the purchasing criteria; moreover, it enables the purchaser to select the most qualified contractor(s). Some examples of RFPs are provided under the resources tab of this reference. Typical sections of an RFP will contain:

- Introduction: background and objectives of the RFP

- Scope of services: objectives of service delivery; what, how many, where, and to whom

- Payment methods: how contracted providers will be paid

- Qualifications: characteristics of providers deemed qualified to submit a proposal

- Proposal format: content specifications and items that should be included in a proposal

- Others: proposal selection criteria, definition of terms, time schedule, contact person, and so on (Liu et al., 2006)

1.5. How can I assess my organization’s capacity to contract for family planning services?

A scan of the external and internal environments can be completed based on desk research (on topics such as those cited in the questions below) and complemented with stakeholder interviews (for example, with Ministry of Health or the Ministry of Finance, donors, and current or prospective clients). These data can provide an initial indication of the level of support and readiness for an SDO to contract out its services and to identify entry points for the SDO to do so.

External scan:

- Current view of the target market (size, demographics, trends

- Regulatory and legal frameworks for provision and financing of health care

- How do relevant socioeconomic factors and health care delivery and financing policy stack up? For example, what is the government’s policy on provision of family planning and reproductive health services? To what extent are family planning and reproductive health services provided in the public versus private sector, and how much cost is borne by clients? What is the role of subsidies and the general availability and stability of sources of funding?

- To what extent is insurance part of either public or private financing mechanisms? How many people are covered and for what benefits or services? How do health care providers participate and how are they compensated?

- To what extent does the government or other purchasers finance service provision through contracts? What is the mix of services and the geographies and target populations that these contracts cover?

- How are existing contracting arrangements set up and performing? What payment mechanisms are in use?

- How are SDOs accredited and evaluated?

Internal scan:

- The perception of the SDO in the market; its strengths and weaknesses

- The experience of the SDO with contracting: With which purchasers? For which services? Under what kind of payment arrangements? How have contracts performed?

- Performance of the SDO with respect to quality of care and client satisfaction

- Costs of the SDO to deliver services; overall financial performance

- Adequacy of SDO operating systems (e.g., finance and accounting, human resources, information systems, and so on)

1.6. What external market indicators are relevant to evaluate the potential and feasibility of contracting? Where are these data found, and how are they interpreted?

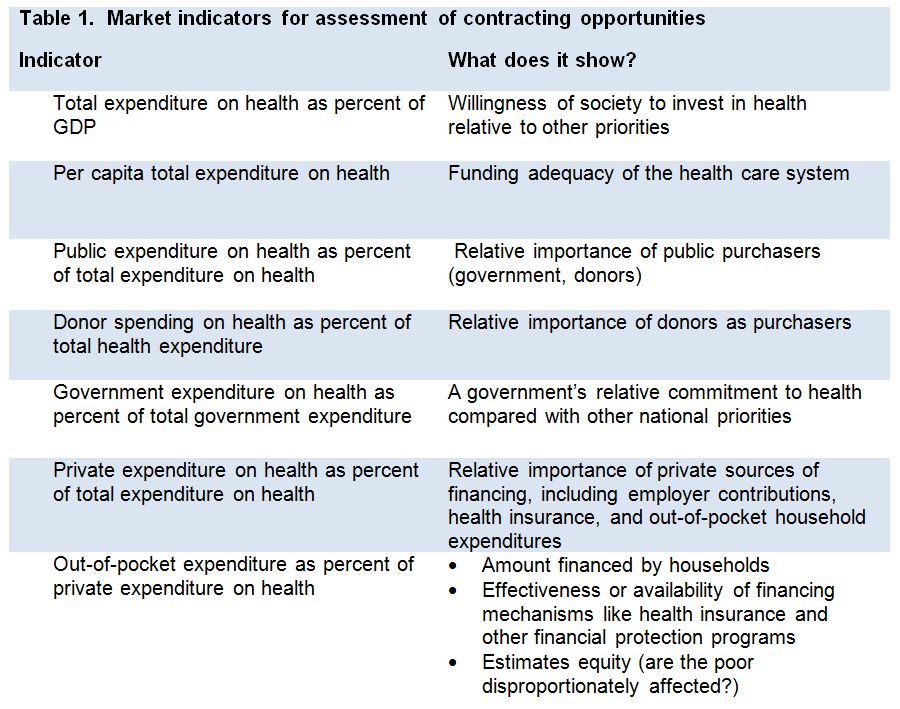

Successful contracting is based on a sound understanding of the market conditions (obtained by performing an external market scan). Table 1 illustrates some market-level indicators that can assist SDOs to evaluate contracting opportunities. Such indicators can allow an SDO to assess the amount and sources of funds allocated to health. Market financing dimensions for SDOs to consider when evaluating contracting opportunities include:

- What are the sources of funding (government, donor, out-of-pocket expenditure, other private sources)?

- What is the amount of funding available and how it is changing?

- To what extent do sector-wide health resources reflect those available for family planning and reproductive health services?

For example, when a market has a low level of financing for health care by public sources, and a significant part of health care expenditure is out of pocket, a prospective contract with a government or donor agency can expand demand for family planning and reproductive health services by reducing financial barriers for clients to access care.

(Source: Marie Stopes International, 2014)

Data sources to obtain market statistics include:

- Health system descriptive studies (WHO/World Bank)

- HS 20/20 health system assessments

- World Bank database

- World Health Organization Health Accounts

- World Health Organization Health Financing International Charts

- World Health Organization Global Health Observatory data

- World Health Statistiscs 2012, Part III - Global Health Indicators

- National Health Sector Strategic Plan

- National Strategic Plan for family planning and reproductive health services

- National policy on public-private partnerships

1.7. When should I decline a potential contracting opportunity?

Not all contracting opportunities are right for an SDO, which should avoid contracting (or seek to adapt the proposal terms to those that are more acceptable) when:

- The contracting opportunity is not sufficiently aligned with the SDO’s mission or business model and lacks strategic importance.

- The SDO’s total costs (direct and indirect) are not sufficiently current and detailed to enable it to accurately price its services (if proposed payment is not cost-based).

- The SDO lacks the capacity to deliver the volume, mix, or geographic access of services expected.

- There is insufficient cost-benefit to enter into the contract (for example, expected volume of services is not expected to offset administrative costs).

- Compliance requirements, like reporting, are not feasible or realistic (for example, criteria to evaluate performance-based payment are not easily or accurately measured) or there are other vague or complex requirements in the contract.

- The capacity and commitment of the purchaser to meet financial obligations and oversee contract performance may be insufficient or too uncertain.

- The contract lacks reasonable exit clauses or would be burdensome to terminate.

1.8. How will a purchaser evaluate my proposal?

Ideally, for purposes of transparency and fairness, purchasers will evaluate RFPs using predetermined criteria and standardized scoring from multiple evaluators. Depending on the size and complexity of the contracting opportunity, the RFP and selection process may include more than one phase. For example, an initial call for expressions of interest may be followed by a more detailed request for information from short-listed respondents. Due diligence performed by a purchaser of prospective contractors may include site visits and interviews of key SDO staff. Audited financial statements may be requested along with other standard information, such as an organization chart, staff roster, fee schedule, and recent statistics concerning the size and scope of the SDO and its operations.

In some situations, such as when a purchaser is unable to manage a competitive tender process or there are too few respondents to an RFP, a purchaser or a donor partner may elect to contract with an SDO via a selective or sole-source approach, whereby an open RFP process is not followed.

In all cases, an SDO should understand how proposals will be evaluated as part of deciding whether to respond to an RFP. Often, there is a possibility to contact the purchaser to clarify the proposal process and to receive important guidance about the contracting opportunity. While cost remains a dominant concern for purchasers, other considerations that are more subjective—including the reputation and capacity of the SDO and the technical merit of the proposal—can lead to selection of a contractor that is not the lowest bidder.

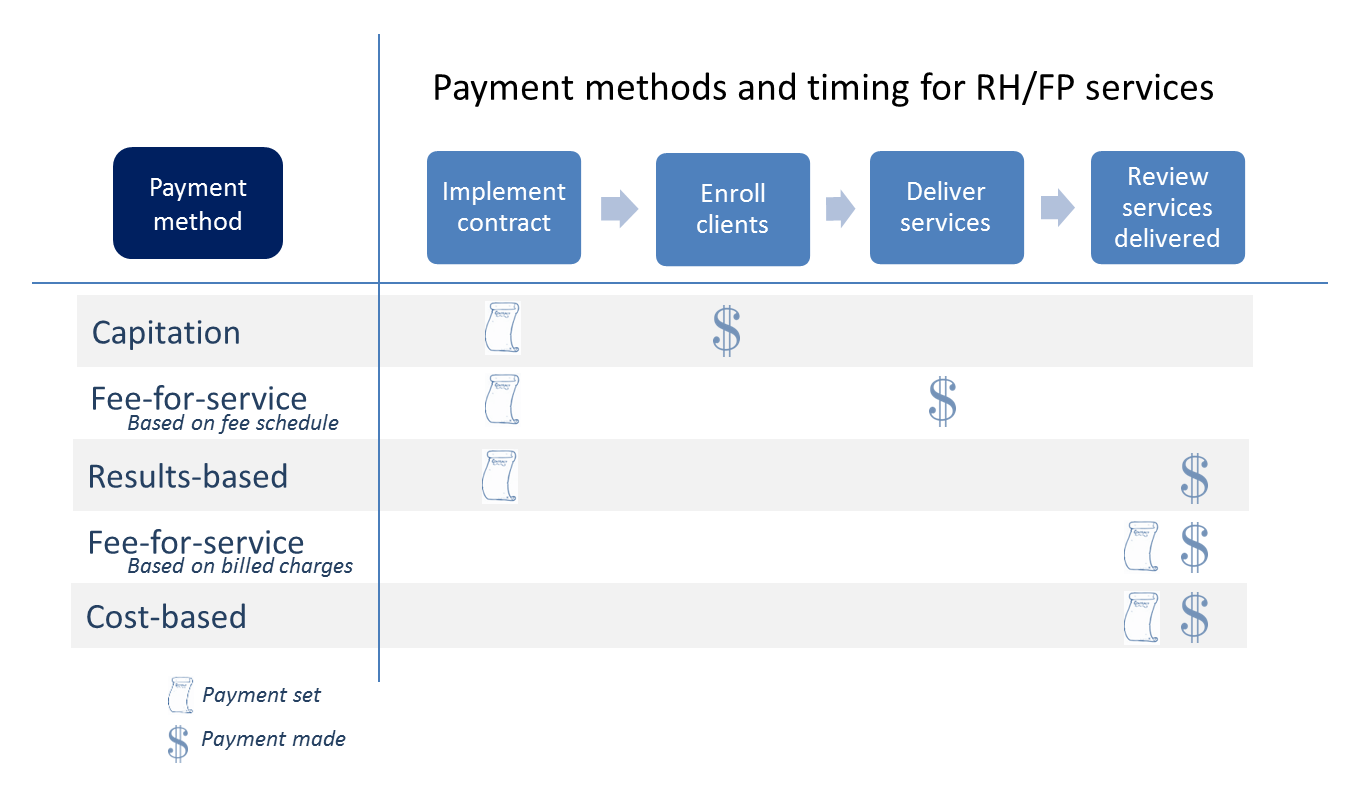

1.9. What are different payment methods I can expect a contract to offer?

Each payment method has pros and cons for purchasers and SDOs and each influences service standards, cost effectiveness, contractor costs, and the quality of services delivered. Increasingly, health services purchasers are seeking performance-based payment methods to align incentives of purchasers and SDOs with desired behavior and outcomes. The type of payment method affects the cash flow and administrative costs of the SDO and thus is a crucial component of any contract.

Payment methods for family planning and reproductive health services may fall into one or more categories (Liu et al., 2006, MSI, 2014):

Capitation

The purchaser pays a lump-sum advance per person, per period based on the number of people assigned to the provider. This means that the amount a provider earns for family planning and reproductive health services is not based on the type of or amount of services provided. Capitation is most common in high income countries but is expanding to other low- and middle-income countries. It is most commonly used to purchase primary care services.

Fee-for-service

Fee-per-service payment models are an output-based payment mechanism in which a purchaser pays the provider per service provided. Fee-for-service payments can be based on a negotiated rate agreed to in advance (i.e., a fee schedule), or based on billed charges set by the provider. They may apply to specific line-item (unbundled) services (e.g., consultations, procedures, and/or supplies), to a pre-determined bundle of services such as a maternity care package consisting of antenatal care and normal delivery, or a day in the hospital.

Results-based

The SDO is reimbursed based on the its performance, as measured by the achievement of predetermined objectives and targets (see FAQ 1.11). A common type of results-based payment method is outcome-based, where the contractor is reimbursed based on the improvement in one or more outcomes (for example, an increase in the number of women returning for a follow-up visit after their first injection of DMPA).

Cost-based

The SDO is reimbursed based on costs incurred to provide contracted services to clients.

Input-based

The SDO is paid a fixed amount to cover input costs (personnel, beds, utilities, equipment, commodities and supplies, and so on) for a defined period of time.

The most common types of payment methods used in contracting are:

- Fee-for-service (also known as payment per service, a discount applied to billed charges, or a fee schedule)

- Per case (also known as a package or case rate) or per diems, in the case of per day payments

- Reimbursement based on costs, salaries, or other inputs

Tips for payment approaches

Tips for payment approaches

- Payments based on outputs help to retain flexibility but require you to know the cost of your services

- Understand a purchaser’s capacity and process to administer funds to predict timeliness and potential delays in payment

- Spread the risks. Try to mix payment advances and reimbursements, especially when dealing with purchasers new to contracting

- Formalize in-kind payments in memoranda of understanding to confirm approximate value of all contributions.